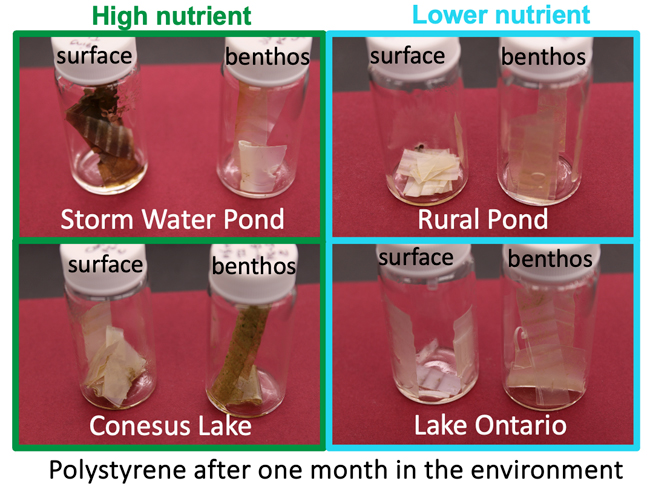

Tyler and her team wanted to evaluate the fate of different types of post-consumer plastic in different receiving waterbodies. Here, at Conesus Lake, they attached plastic swatches and particles to frames that were either affixed with floats or anchored to the bottom of the lake. They repeated the procedure in four additional waterbodies in the Lake Ontario watershed. They evaluated degradation, formation of biofilm and the microbial composition of the biofilm, changes in toxicity to the model organism Lumbriculus variegatus, changes in settling velocity, and a variety of other metrics. Together, this suite of variables gave them insight into the fate and impact of different kinds of plastic in the Great Lakes Basin. Credit: Steven Day

— By Chris Gonzales, Freelance Writer, New York Sea Grant

Contact:

Lane Smith, Research Program Coordinator, NYSG, E: lane.smith@stonybrook.edu, P: (631) 632-9780

Scientists have been studying what is happening to the muddy bottoms of lakes, streams, and rivers as they get invaded by plastic pollution

Rochester, NY, February 18, 2025 - At the muddy bottoms of lakes, streams, and rivers, you’ll find a surprisingly active community of living things. Scientists call this area the “benthos,” and it’s an important part of ecosystem functioning. Many sensitive organisms live in this aquatic zone at the very bottom, and the health of these organisms is often seen as a good indicator of overall environmental health1. Christy Tyler and her team have been working on studying what is happening to the benthos as it gets invaded by plastic pollution.

Tyler is an ecologist and professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology, and her research is supported in part by New York Sea Grant. She and mathematician Matthew Hoffman, also at RIT, lead an interdisciplinary team of researchers and educators investigating plastic pollution in the Great Lakes.

The team is trying to fill in gaps in our understanding about where certain types of plastic might go and what impact they have on the ecosystem after they enter our lakes and watersheds. Different plastics have different characteristics, including how buoyant they are, what types of additives are in the plastic, and what form they are in. The RIT team conducted a series of experiments to understand what happens to different kinds of plastic once they enter the environment and then created computer models to predict what may happen to plastic once it enters the Great Lakes.

Scientists incubated pieces of polystyrene cups in different water bodies for one month. Note the differences in the growth of biofilm on the surface of the plastic and the different levels of yellowing, which is indicative of UV oxidation of the plastic. Yellowing is greatest at the surface, but where nutrient levels and biofilm growth are high, less oxidation occurred suggesting that the plastic will break down into smaller pieces more slowly. Credit: Nathan Eddingsaas

Tracking the discarded plastics

The team is using a broad approach to study plastics not only in and across Lake Erie and Ontario, but in their watersheds. The Lake Ontario Watershed alone is a 2,460-sq-mile area with almost six thousand miles of freshwater rivers and streams running into it2. Her team studied what happens to plastic in five sites: Lake Ontario; one of the Finger Lakes; a stormwater retention pond; a rural pond in the watershed; and a quarry pond.

One thing that often happens to discarded plastics is “biofouling,” when they become covered with microbes like bacteria and algae. This organic coating may influence the impact that plastic particles might have on ecosystems and may also change the density of the particles so that they sink to the bottom. Generally speaking, plastic particles tend to move closer to the shore and become beached. The denser particles tend to sink to the bottom. Buoyant plastics that become biofouled by algae and microbes may grow denser and are thus more likely to settle in the benthos. But some polymers are already more dense than water and sink quickly, with potentially more rapid impacts on the benthic community.

The team also found that the community of organisms that grows on plastics varies depending on both the kind of plastic and what type of water body the plastic first enters. Bacteria growing on plastic in stormwater ponds are different than those growing on plastic directly entering Lake Ontario, and may have more species that are pathogenic—and might cause disease. The particles may also become more or less toxic over time. Plastic particles tend to attract other contaminants already in the water, and might serve to concentrate or move toxins around. Thus, knowing where the particles are likely to end up is important for understanding where the risks might be highest.

These results were used to refine the computer models that Dr. Hoffman and his students hope will help us understand how buoyant particles such as polyethylene, a common plastic, might persist at the muddy bottom, or become buoyant and rise again to the surface of lakes, eventually becoming beached on the shore. If Lake Erie and Ontario have different biofouling patterns, which is possible given the different environments in the Lakes, there may also be different patterns of plastic dispersal. The models found that a majority of plastics that are buoyant, about 70 to 80 percent of them, end up on beaches. Also, beached plastics tend to be concentrated around urban centers rather than distributed evenly throughout the lake.

Sharing the results

In conclusion, she and her team emphasize that plastic is a catch all term for many, many different kinds of materials that vary in composition. As a result, different types of plastics behave differently in the environment and pose different risks for ecosystems and people.

“Because of the complexity associated with plastic and the variability in the ways it enters our environment,” Tyler noted, “having an interdisciplinary team comprised of ecologists, engineers, mathematicians, chemists, and biochemists is critical in order to gain a full understanding of the threat of plastic pollution to the Great Lakes.”

You can learn more about Tyler and her research team’s efforts. Their website is: www.rit.edu/plasticpollution

References

1 Understanding the World of benthos: an introduction to benthology - ScienceDirect Retrieved June 6, 2024

2 Lake Ontario And Minor Tributaries Watershed - NYSDEC Retrieved June 6, 2024

More Info: New York Sea Grant

Established in 1966, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s National Sea Grant College Program promotes the informed stewardship of coastal resources in 34 joint federal/state university-based programs in every U.S. coastal state (marine and Great Lakes) and Puerto Rico. The Sea Grant model has also inspired similar projects in the Pacific region, Korea and Indonesia.

Since 1971, New York Sea Grant (NYSG) has represented a statewide network of integrated research, education and extension services promoting coastal community economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

NYSG historically leverages on average a 3 to 6-fold return on each invested federal dollar, annually. We benefit from this, as these resources are invested in Sea Grant staff and their work in communities right here in New York.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries, federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers, educators, the media and the interested public.

New York Sea Grant, one of the largest of the state Sea Grant programs, is a cooperative program of the State University of New York (SUNY) and Cornell University. The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY Buffalo, Rochester Institute of Technology, SUNY Oswego, the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office in Newark, and in Watertown. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook University and with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Nassau County on Long Island, in Queens, at Brooklyn College, with Cornell Cooperative Extension in NYC, in Bronx, with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Ulster County in Kingston, and with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Westchester County in Elmsford.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org, follow us on social media (Facebook, Twitter/X, Instagram, Bluesky, LinkedIn, and YouTube). NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which it publishes 2-3 times a year.